Beyond the Optics — Vietnam and the Semiconductor Race

— Vanguard Editorial Board

December 30th 2025

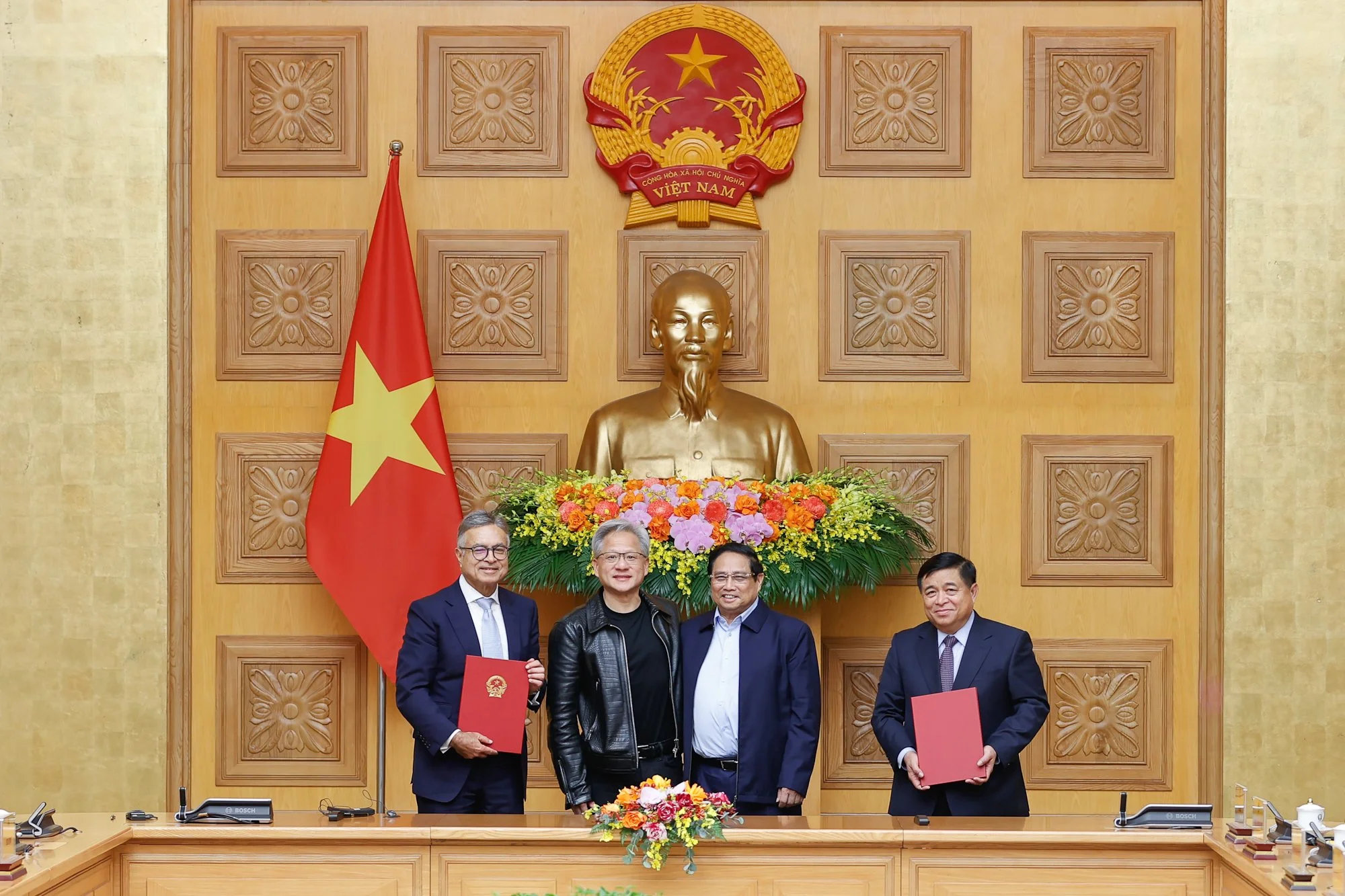

On December 5, 2024, the visit of Jensen Huang, Founder, President and CEO of NVIDIA, briefly placed Vietnam in the global technology spotlight. The day’s formal announcement—cooperation between NVIDIA and the Vietnamese government on AI research, development, and data infrastructure—was strategically meaningful, if unsurprising.

What followed mattered more.

Images of Huang walking Hanoi’s streets, drinking beer, and speaking casually with Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính spread rapidly across social media. The scenes were disarming, informal, and instantly symbolic. For many observers, they appeared to mark Vietnam’s arrival in the global semiconductor conversation—a visual shorthand for technological relevance and geopolitical alignment.

But symbolism travels faster than capability.

No photograph, no partnership, and no declaration—however well received—changes a country’s semiconductor position overnight. Industrial capacity is not built through moments, but through decades of disciplined investment in talent, systems, and execution. Global firms can signal intent; they cannot outsource national capability.

One year later, the more useful exercise is not celebration but calibration. Where does Vietnam actually sit within the semiconductor value chain today? What parts of the industry are structurally within reach, and which remain far beyond it? And after the enthusiasm fades, what choices must be made to prevent ambition from outrunning reality?

Vietnam’s semiconductor future will not be decided by how it is seen—but by what it is able to build.

What opportunity does Vietnam really have?

According to the latest report from the U.S. Semiconductor Industry Association, the global semiconductor market has surpassed US$600 billion. As Trần Đăng Hòa, Chairman of FPT Semiconductor, has noted, semiconductors underpin the entire electronics and electrical sector as well as the internet-connected device ecosystem—together worth roughly US$2 trillion. They also sit at the core of industrial manufacturing, an arena estimated at US$6 trillion. As automation and artificial intelligence continue to expand, demand for chips is rising at an exponential pace.

In today’s global semiconductor landscape, the value chain is clearly structured. Companies from the United States, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Europe dominate different segments. Design typically accounts for around 50% of total industry revenue, manufacturing about 40%, and packaging and testing roughly 10%. Each link requires high standards, massive capital, and deep operational experience—conditions that have limited the participation of developing economies for decades.

A rare opening emerged after the COVID-19 pandemic, when geopolitical tensions and technology rivalry among major powers forced a reconfiguration of global supply chains. To reduce risk, certain links began to shift geographically.

In Vietnam, semiconductors returned to the spotlight following the announcement of the Vietnam–United States Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2023. Jensen Huang’s sidewalk beer in Hanoi a year later merely reinforced the perception that Vietnam’s semiconductor moment was approaching. At the same time, the government set a target of training 50,000 semiconductor engineers by 2030, fueling expectations of a workforce large enough to play a long game.

Public interest in the sector is driven by big hopes: attracting higher-quality FDI; shifting the growth model; accelerating digital transformation; repositioning exports; upgrading workforce skills; and catalyzing education reform. Vietnam already hosts more than 40 chip-design companies, including around 30 high-profile foreign firms, alongside major players in packaging and testing such as Intel, Amkor Technology, and Hana Micron Vina.

Against this backdrop, Vietnam’s questions must become more practical: given the industry’s structure and Vietnam’s specific advantages, where can the country truly embed itself in the value chain? What conditions are essential to gradually build autonomous capabilities? And after strong statements of national resolve, what should come next?

“I emphasize the word easy deliberately. Investors evaluate countries through experience. Easy entry is visas and immigration. Easy living is safety and amenities. Easy working is digital infrastructure and procedures. And most important of all is easy exit.”

— Jason Hoang, CEO of Investream

Vietnamese people make Vietnamese semiconductors

The modern history of Vietnam’s semiconductor industry can be traced to 2004, when Renesas Design Vietnam was established. A subsidiary of Japan’s Renesas—then valued at nearly US$22 billion and a global leader in microcontrollers (MCUs) and system-on-chip (SoC) solutions for automotive, industrial, and IoT applications—this marked a pivotal moment.

For Vietnam’s nascent industry, Renesas was not merely a company but the single most important training ground for talent. With the long-term, methodical approach typical of Japanese corporations, Renesas maintained a rigorous three-phase internal training program, educating 70–100 engineers annually. Initially, experts from Japan taught directly. After more than five years, Vietnamese engineers matured enough to lead training themselves and collaborate with universities to standardize IC design curricula.

An estimated half of today’s high-quality IC design engineers in Vietnam have passed through Renesas Vietnam.

As Vietnamese engineers gradually matured, a positive domino effect followed. Numerous international semiconductor companies entered Vietnam. Early cohorts trained by FDI firms became the core workforce founding or leading local design houses such as VnChip, Wavelet, and Saigon Silicon—or working at global giants.

Overseas Vietnamese experts returning home, including figures such as Trịnh Xuân Lạc, Trần Duy Tân, and Lê Quang Đạm, also played a crucial role in building the sector.

These dynamics have produced a growing design cluster of roughly 40 companies. At its core are around 30 foreign-invested firms—well-known names such as InPhi/Marvell, AMCC/Ampere, Active-Semi/Qorvo, Microchip, Synopsys, and more recently Cadence and CoAsia Semi.

Yet the greatest source of pride is not the company names but the nearly 7,000 design engineers—Southeast Asia’s second-largest such workforce after Singapore, far ahead of the rest of the region. This is Vietnam’s true gold: human capital in research and design, the segment that captures roughly half of the semiconductor value chain.

“Political stability is necessary, but it has never been sufficient. Investors need a predictable legal system, contracts that are enforced to the end, and assurance that capital will not be trapped by unexpected barriers midway through an investment.”

—Babak Dastmaltschi, former head of wealth management at Credit Suisse and UBS

Arnaud Ginolin, Head of BCG Vietnam

_________________

Three benchmark international financial centres: Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Their common denominator was not scale or geopolitics, but institutional design from the outset. All operate under English common law, aligned with global financial standards, and function as legal enclaves with a high degree of autonomy, including independent courts — a foundation critical to international investor confidence.

_________________

The capability gap

In chip manufacturing, which accounts for about 40% of total value, Vietnam has almost nothing. Some sources classify Besi (Netherlands) under this segment, but in reality Besi is a supplier of packaging and testing equipment.

In packaging and testing (OSAT), which contributes around 10% of value added, Vietnam has attracted several major projects:

Intel has invested roughly US$1.5 billion in a packaging and testing facility at Saigon Hi-Tech Park.

Amkor operates a plant in Bắc Ninh with initial registered capital of about US$530 million and a long-term commitment of up to US$1.6 billion.

Hana Micron runs a packaging and testing facility in Bắc Giang with a total investment of US$930–950 million.

Kyocera has invested US$400 million in a semiconductor packaging materials plant in Hưng Yên.

Besi operates a machinery plant for packaging and testing at Saigon Hi-Tech Park, with an initial investment of about US$4.9 million and an expansion pipeline of US$42 million.

According to many industry experts and leaders, OSAT projects remain fundamentally pure FDI plays. The state provides incentives in tax, electricity, and land; foreign firms decide to invest—or not—based on profitability. When market conditions are favorable, they expand; when not, relocation to other countries is always an option.

For Vietnam, beyond capital inflows and tax revenue, the greatest value lies in the training of engineers and high-skill technicians under modern production processes—currently numbering around 8,000 people.

That said, knowledge spillovers remain limited. Most OSAT processes are highly automated; labor focuses on operating production lines rather than accessing core knowledge such as design, R&D, or chip development.

Moreover, packaging and testing plants require massive infrastructure: high-capacity power, ultra-pure water, and tightly controlled environments. A large packaging line can consume tens of megawatts, making power supply, redundancy, and electricity costs decisive factors in long-term viability.

This is not a natural advantage for Vietnam. Even with several large projects, the long-term contribution of OSAT to domestic technological development remains contested. In the coming years, Vietnam also faces localized power shortages—particularly in the North—making energy security a prerequisite for any semiconductor ambition.

Another frequently cited factor is Vietnam’s rare earth reserves. While substantial, these resources have not translated into deeper participation in semiconductor supply chains. Extraction requires sophisticated separation technologies and refining ecosystems in which China currently holds overwhelming dominance. Environmental costs and high-tech investment mean Vietnamese rare earths cannot yet compete on price with China’s mature, large-scale industrial chain.

The foundry debate

From a corporate perspective, Lợi Nguyễn, Senior Vice President at Marvell Technology, argues that Vietnam has chosen focus over dispersion. “The semiconductor industry is inherently brutal,” he says. “Customers care only about the leader, or at most the second or third player with at least 30% market share. Below that threshold, losses are almost guaranteed.”

He cites Malaysia as an example: the government spent tens of billions of dollars developing a semiconductor complex in Penang, aiming for foundry capabilities. But most output remained in third- or fourth-tier segments, unable to compete. Massive investments in infrastructure, materials, chemicals, and equipment failed to generate commensurate value, because the market pays only for the best products; older, cheaper chips are “so cheap that no one buys them.” Malaysia absorbed the losses.

From this perspective, Nguyễn warns against the allure of foundries—a segment representing about 30% of the value chain and currently dominated almost entirely by Taiwan and South Korea.

Still, among Vietnamese entrepreneurs and engineers, the belief that “we must have a foundry” remains strong. Đỗ Minh Phú, CEO of startup Wavelet, hopes Vietnam will one day own a chip fabrication plant to complete the process domestically.

Nguyễn Bảo Anh, who once led Vietnamese engineers in designing Intel’s 3-nanometer chips, goes further: if Vietnam seeks true technological self-reliance, a foundry is indispensable. In his view, this can only happen through state-led investment, not isolated corporate efforts.

Despite their skills, Vietnamese engineers are rarely entrusted with entire high-value projects. Multinational corporations allocate work based on trust and IP protection. Many Vietnamese engineers excel in supporting roles but have limited access to core design or critical IP. This slows knowledge accumulation and technological maturation—unless Vietnam develops its own core design and manufacturing capabilities through domestic R&D centers and foundries.

Without its own research and production base, Vietnam will remain dependent. Global firms have little incentive to bring their most valuable projects or transfer full technology stacks. Vietnamese talent risks being confined to lower-value tasks, unable to climb the global value ladder.

“Building an international financial centre is not a short-term exercise. It is a multi-decade journey. In the early phase, a geographically limited and functionally specialized model is both more realistic and more credible.”

— Chua Hak Bin, Chief Economist for ASEAN at Maybank Kim Eng

_________________________

The next step

A pragmatic option—endorsed by many experts—is to build a small-scale manufacturing and research cluster (labs, pilot foundry) for experimental purposes, rather than pursuing grand ambitions from the outset. This infrastructure is essential for a self-reliant, sustainable semiconductor future. The state would need to act as midwife, as losses are almost inevitable.

In recent statements, the Prime Minister has affirmed a goal of operating Vietnam’s first semiconductor manufacturing plant by 2026–2027. The state has approved financial support of up to VND 10 trillion (approximately US$400–450 million) for the project.

While the government’s resolve is clear, this sum is small relative to the real cost of a wafer fab or internationally scaled R&D center. Domestic private firms struggle to mobilize multi-billion-dollar capital for high-risk, long-payback projects. This policy gap must be addressed if Vietnam intends to move deeper into higher-value segments.

Vietnam has rare earths but lacks large-scale refining plants. Viable options include joint ventures for clean refining technology onshore, or raw exports tied to long-term supply agreements with foreign refiners—both demanding stringent environmental governance and investment commitments.

Above all, continued investment in people is paramount. Vietnam currently has around 7,000 design engineers and roughly 8,000 engineers and technicians in packaging and testing. With systematic investment, this workforce can grow further. Industry consensus is clear: human capital is the only truly sustainable foundation.

Yet the target of 50,000 semiconductor engineers by 2030 is daunting. Current numbers stand at roughly 15,000 across design and OSAT, leaving a vast gap with less than five years remaining.

The challenge is not just quantity but quality. Semiconductors demand engineers with strong foundations in mathematics, physics, and electronics, while universities are still in early stages of building internationally standardized programs.

Vietnam can buy value chains and import machines. What it cannot shortcut is human capability. In the end, it is the depth of Vietnamese engineers—not viral moments or diplomatic symbolism—that will determine Vietnam’s place in the global semiconductor industry.