Why Vietnam’s IFC Has Yet to Convince Global Capital

Vietnam has formally launched its International Financial Centre. Market reaction so far suggests that credibility, not declarations, will determine whether global capital follows.

— Vanguard Editorial Board

December 24th 2025

_____________________

Editor’s Note

This editorial examines how international capital markets typically respond in the early stages of building an international financial centre. It draws on conversations with global asset managers, bankers, and institutional investors active across Asia. The analysis focuses on structural and market dynamics rather than policy intent, and should be read as an assessment of execution challenges common to late-entrant financial centres.

_____________________

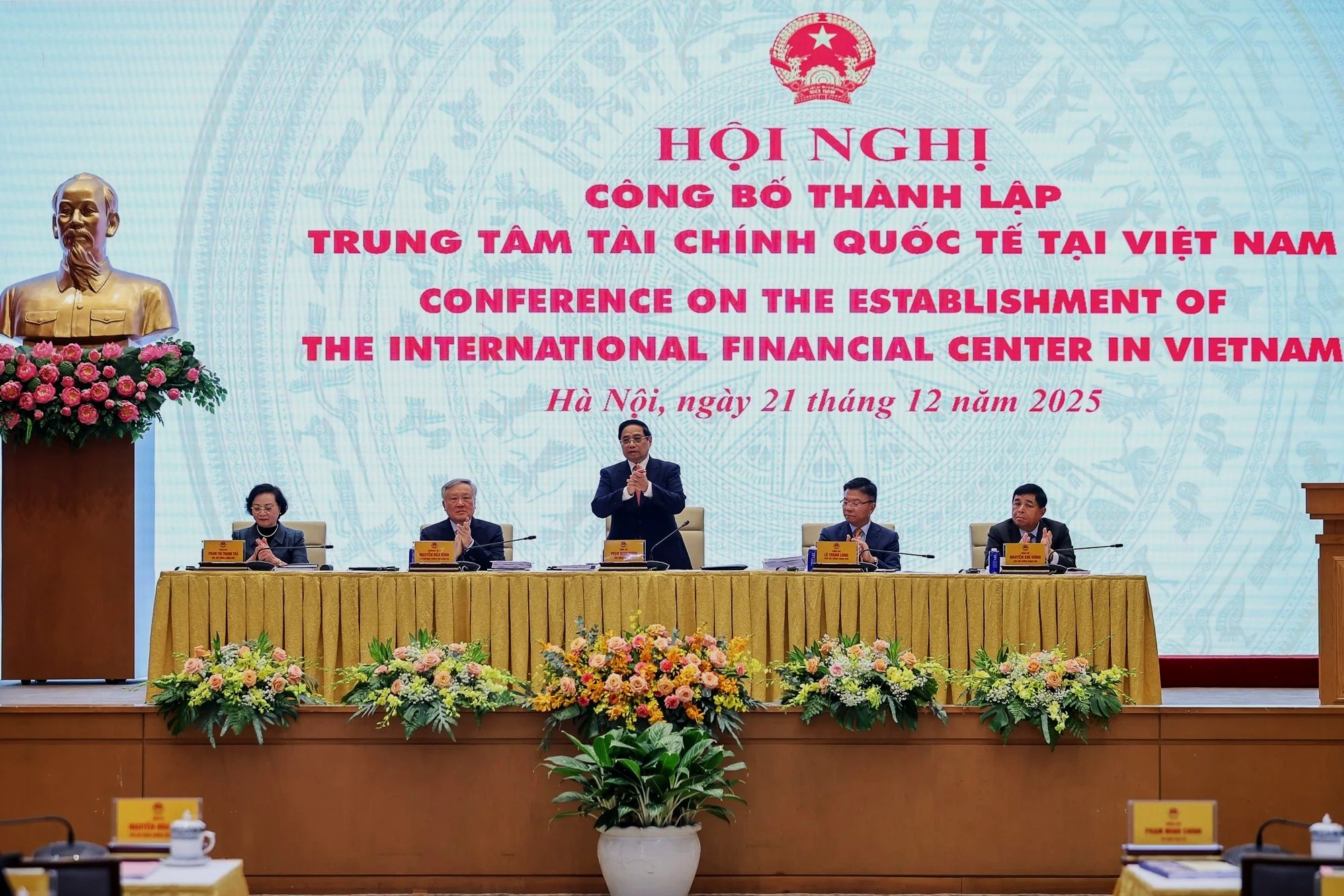

On the morning of December 21, 2025, the Vietnamese government officially announced the establishment of an International Financial Centre (IFC). The decision, prepared over many months, marked a significant political milestone and signaled clear intent to deepen Vietnam’s financial integration. Initial domestic sentiment was broadly positive, particularly among local businesses and property developers.

Markets, however, operate on a different clock.

In the days following the announcement, there was no clear surge of interest from international financial institutions. No visible movement of major capital flows. Nor were there signs of “reverse roadshows,” where global investors proactively seek clarity on rules, protections, and exit mechanisms.

This contrast has been noticeable. Earlier in the year, when the IFC received in-principle approval, optimism emerged that Vietnam was preparing for a meaningful institutional leap. That enthusiasm has since cooled into watchful caution. Some potential participants say they are monitoring developments closely — but for now, little more than that.

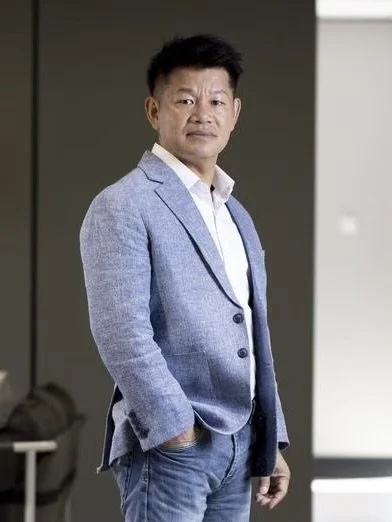

“All the information around Vietnam’s IFC today feels like a black hole,” said Jason Hoang, CEO of Investream. “You look into it, but you still can’t see a concrete shape.”

Hoang recently returned to Ho Chi Minh City after more than a decade abroad, flying in from Singapore, where his fund is headquartered. He previously worked directly with officials and specialists from the Da Nang People’s Committee during early preparations for the IFC. In his view, the city has changed rapidly and deserves credit — but becoming a genuine international financial centre still requires four basic conditions: easy to enter, easy to live, easy to work, and easy to exit capital.

“I emphasize the word easy deliberately,” he said. “Investors evaluate countries through experience. Easy entry is visas and immigration. Easy living is safety and amenities. Easy working is digital infrastructure and procedures. And most important of all is easy exit.”

For global asset managers, international banks, and investors capable of deploying billions of dollars, additional decrees or political declarations alone do little to build confidence if the operating experience remains unchanged.

“I emphasize the word easy deliberately. Investors evaluate countries through experience. Easy entry is visas and immigration. Easy living is safety and amenities. Easy working is digital infrastructure and procedures. And most important of all is easy exit.”

— Jason Hoang, CEO of Investream

Still a capital problem

Over the remainder of this decade, Vietnam’s demand for capital will be substantial. Estimates suggest that to sustain growth approaching 10% during 2026–2030, the economy will require between USD 1.4 and 1.5 trillion in investment. Put differently, generating one dollar of growth may require five to six dollars of capital.

Without institutional conditions capable of absorbing long-duration capital, this financing gap cannot be bridged domestically.

In theory, the IFC should be part of the answer: a platform designed to attract long-term, globally mobile capital through a framework governed by rules aligned with international standards. It is an attractive proposition. In practice, it is difficult to realize.

After more than two decades managing wealth for ultra-high-net-worth clients at Swiss banks, Babak Dastmaltschi, former head of wealth management at Credit Suisse and UBS, argues that incentives and political messaging play only a secondary role.

“Political stability is necessary, but it has never been sufficient,” he said. “Investors need a predictable legal system, contracts that are enforced to the end, and assurance that capital will not be trapped by unexpected barriers midway through an investment.”

In his view, an IFC only matters if it functions as a controlled experimental zone — one that allows higher standards of international arbitration and capital mobility to operate in practice.

“If it’s called a sandbox but lacks real authority, markets will recognize that quickly. Smart money moves ahead of policy announcements.”

Hoang shares this assessment. For him, the IFC is ultimately a test of how far Vietnam is willing to relax capital controls and delegate authority in exchange for global capital.

“Markets don’t demand perfection,” he said. “But they are extremely sensitive to ambiguity.”

The true measure of confidence, according to investors, lies in the operational details that have yet to fully emerge: foreign-exchange mechanisms, the degree of capital mobility, dispute-resolution processes, and — above all — how much real legal and operational autonomy the IFC will possess.

“Political stability is necessary, but it has never been sufficient. Investors need a predictable legal system, contracts that are enforced to the end, and assurance that capital will not be trapped by unexpected barriers midway through an investment.”

—Babak Dastmaltschi, former head of wealth management at Credit Suisse and UBS

Arnaud Ginolin, Managing Director & Partner— BCG Vietnam

_________________

Three benchmark international financial centres: Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Their common denominator was not scale or geopolitics, but institutional design from the outset. All operate under English common law, aligned with global financial standards, and function as legal enclaves with a high degree of autonomy, including independent courts — a foundation critical to international investor confidence.

_________________

Three cities, one kind of foundation

When discussing what makes a legal system predictable and contracts enforceable, Arnaud Ginolin, head of Boston Consulting Group in Vietnam, points to three benchmark international financial centres: Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

Each developed along a different path. Dubai tied its IFC to commodities trading and regional logistics. Singapore focused on asset management and capital intermediation, with assets under management estimated at around USD 5 trillion. Hong Kong established itself as a capital-markets gateway between Mainland China and the world.

Their common denominator was not scale or geopolitics, but institutional design from the outset. All operate under English common law, aligned with global financial standards, and function as legal enclaves with a high degree of autonomy, including independent courts — a foundation critical to international investor confidence.

Hybrid IFC models, where the state retains tighter control, are possible, Ginolin notes. But the trade-off is clear: reduced attractiveness to global capital and a more limited role in the regional financial system.

Vietnam is far from alone in pursuing this ambition. International financial centres have been built over decades, and competition among them has intensified. Institutional credibility and speed of execution now matter more than intent.

According to the Global Financial Centres Index, while dozens of financial centres exist worldwide, only around 30% are widely recognized by markets as functioning international financial centres. Self-designation alone does not confer status.

The resolve required of late entrants

The historical trajectories of London, New York, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Dubai reveal a broadly consistent pattern. Financial centres tend to evolve from domestically focused systems with tight capital controls, to early-stage IFCs with limited foreign participation, then to regional hubs, and finally — in rare cases — to global centres where capital moves freely and assets are priced internationally.

Ho Chi Minh City remains firmly in the early stage.

Most successful centres required decades to establish their position, and many never progressed beyond the initial phase. In practice, only New York and London are widely regarded as true global financial centres. Hong Kong and Singapore follow closely as powerful regional hubs with some global reach.

“The places that succeeded all started narrow — but executed relentlessly,” Ginolin observed. “The difference lies less in ambition than in choosing the right focus and pursuing it consistently.”

Vietnam enters the IFC race amid intense regional competition for capital, without yet clearly defining its comparative advantage. Compared with established centres, its current model remains exploratory, with several core elements still undefined.

Chua Hak Bin, chief economist for ASEAN at Maybank Kim Eng, has previously cautioned that expectations of a fully functioning IFC within a short timeframe are overly ambitious.

“Building an international financial centre is not a short-term exercise,” he has argued. “It is a multi-decade journey. In the early phase, a geographically limited and functionally specialized model is both more realistic and more credible.”

“Building an international financial centre is not a short-term exercise. It is a multi-decade journey. In the early phase, a geographically limited and functionally specialized model is both more realistic and more credible.”

— Chua Hak Bin, Chief Economist for ASEAN at Maybank Kim Eng

_________________________

Toward the necessary conditions

Over the long term, any IFC roadmap must move toward greater currency convertibility within its designated zone if it is to catalyze genuine international financial activity.

For an economy that continues to prioritize macroeconomic stability, lacks a fully convertible currency, and has relatively shallow capital markets, loosening capital controls inevitably raises policy risks. Yet debate without experimentation leads nowhere — and the IFC is meant to function as that pressure valve.

A domestic policy expert involved in the IFC process, speaking anonymously, put it bluntly:

“No one believes Vietnam can fully liberalize capital overnight. But if the IFC does not offer genuine experimental space, then no matter how polished the design, markets will see it as a showcase project.”

The greater risk, he argued, is not failure but half-measures.

“International finance is extremely sensitive to ambiguity. If trust is not established early, correcting course later becomes far more difficult.”

For private investors, the IFC risks irrelevance if it is perceived primarily as a real-estate expansion, measured by land area or skyscraper counts.

Ali Ijaz Ahmed, chairman of Makara Capital and a long-time conduit of capital from Singapore and the Middle East into Southeast Asia, argues that the decisive factors lie elsewhere.

“An IFC is not about building glossy towers,” he said. “It’s about protecting capital, safeguarding intellectual property, and — above all — protecting trust.”

He points to the reality that many Vietnamese startups still relocate intellectual property ownership offshore to attract foreign investment. Value is created domestically, but recorded elsewhere. If the IFC cannot address this, it will struggle to retain knowledge-based value within the economy — a more consequential failure than any delay in construction.

The final measure

When, then, can Vietnam be said to have succeeded in building an international financial centre — when new policies are issued, or when capital stays, operates, and compounds within the system?

Hoang believes the clearest signal will be whether Vietnam can attract a globally significant anchor institution willing to commit real capital.

“A major international institution prepared to place a genuine bet on Vietnam would serve as a trust anchor for the broader ecosystem,” he said. “Capital doesn’t follow master plans. It follows credible leaders.”

This view is shared by Chua, who has argued that every successful international financial centre ultimately required a “mother ship” — a large foreign financial institution willing to commit early and at scale, drawing talent, investors, and ancillary services in its wake.

“In manufacturing, Samsung played that role,” Chua has noted. “In finance, Singapore’s private banking ambitions took a decisive step forward when UBS established its Asian headquarters there.”

Such commitments, however, are contingent on trust in the institutional environment. Investors must be comfortable with the legal and regulatory regime under which an IFC operates. New dispute resolution or arbitration mechanisms, Chua adds, do not build credibility on design alone — they must be tested in practice.

The announcement of the IFC marks a political milestone. Turning it into a financial one will depend less on the volume of decrees than on execution — on the ability to operationalize authority, manage policy risk, and uphold rules that remain predictable over time.

In finance, ideas are plentiful. What is scarce is commitment strong enough for markets to place real money behind them. Vietnam’s IFC now stands precisely at that threshold.

____________________________

— Vanguard Editorial Board

December 24th 2025

___________________

A major international institution prepared to place a genuine bet on Vietnam would serve as a trust anchor for the broader ecosystem. Capital doesn’t follow master plans. It follows credible leaders.

___________________

Chua Hak Bin, chief economist for ASEAN at Maybank Kim Eng